“There is a cleanliness, a breadth and sweep and strength in the North, a purifying realization that one is living close to the fundamental elements of life. Yes, the North has a spell.”—Eric Sevareid

It was during the spring of 1930 when 19-year-old Walter “Walt” Port thought of the idea. He was scheduled to graduate from high school in a few months, so why not celebrate that accomplishment with an extended canoe trip, and do it with his closest high-school buddy, 17-year-old Eric Sevareid?

“We’ll leave right after graduation in June,” Walt explained to Eric. “From here in Minneapolis, we’ll paddle up the Minnesota River to Big Stone Lake on the South Dakota line, then into the Red River of the North, down that river into Canada and Lake Winnipeg, up the east shore of the lake to Norway House and, at that point, attempt a wilderness jump of 500 miles to Hudson Bay. So, what do you think?”

What the young men were considering was a 2,250-mile canoe trip that, as far as they knew, had never before been attempted—or if it had, such a trip had never been documented. And though they would be leaving near the beginning of summer, they would be fortunate to complete such a trip by the time winter arrived in the North.

Sevareid didn’t hesitate. “I’m in!” he said.

But how to pay for such a lengthy trip? As the editor of the high school newspaper, Eric had an idea. He approached W.C. Robertson, managing editor of the Minneapolis Star newspaper, and asked him to sponsor the trip in exchange for stories Eric would write and submit along the route. After mulling over the proposal for a week, Robertson agreed.

“All right, boys, we’ll ride with you,” he said. “I’ll pay a total of $100 for stories filed weekly, or whenever you can manage to find a post office and send one home.”

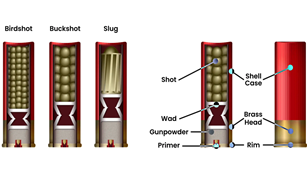

The two young men were giddy with excitement. They set about gathering the necessary equipment, their first purchase being an 18-foot, secondhand, canvas-covered canoe missing its center thwart. Christened the San Souci, meaning without care, they painted on her sides the trip’s objective: Minneapolis to Hudson Bay. In addition to a couple of knives and a hatchet, the only weapon against the wilderness the boys packed was a small, single-shot, .22-caliber rifle.

From the beginning, most people who heard about the canoe trip advised them not to go—it was just too dangerous, they wouldn’t make it. Those naysayers included some of their teachers, even their football coach. But both boys’ dads were encouraging, wishing they could go along, as well.

The San Souci and its two young voyageurs slipped into the water of the Mississippi early on the morning of June 17, 1930. Riding the current downstream a mile, they turned upstream into the Minnesota River, which empties into the Mississippi at Minneapolis. After many weeks of planning, the boys were finally off. But even they had nagging doubts, with Eric later remembering:

“How much easier it is to sit in a chair at home and read about ‘the things to do when camping.’ Things look so easy in print, but when the tent won’t go up, when the beans tip over in the fire, when the water won’t boil and it suddenly begins to rain in the midst of supper, then all the directions in the world won’t help and it’s every man to his own method. For Walter and I, when we started out, knew practically nothing of woods life. Never before had we really traveled by canoe. So everything we learned at first hand, and many were the scars, burns, cold meals and miserable nights that accumulated before all the lessons were learned.”

The first half of the trip was mostly through farm country, with easy paddling and frequent stops at small towns and villages to buy additional food, fill their water container from a farm pump, or maybe even indulge in a Sunday meal purchased at a local diner. Their biggest problems were the summer heat, sunburn and mosquitos. But the challenges would gradually change as they slowly paddled north.

At the Canadian border on August 12, about 1,000 miles into the journey, they cleared customs at Emerson, Manitoba. The customs official told them they were the first to enter Canada through his station by canoe since that particular office had been established. After a quick, cursory inspection of their gear, all the agent requested was a brief ride in their canoe, which the boys gladly obliged.

They next entered Lake Winnipeg, Cree Indian language for muddy water. An immense body of water totaling nearly 9,500 square miles, the lake is relatively shallow, known for its sudden storms that can quickly form huge waves. It’s no place for novice canoeists to be caught offshore. Not surprisingly, our intrepid travelers battled 5-foot swells. That night, Sevareid wrote in his journal, “Walt and I came as close to death today as I ever wish to be.” There is no mention on their equipment list that the boys bothered to pack lifejackets.

The pair stopped at Hudson Bay Company outposts along the way whenever they encountered one, which was not often. An interesting sidenote is that each outpost kept 20 or more carrier pigeons on hand in case of emergencies. For instance, whenever a floatplane left an outpost on fire patrol or some other errand, it always took along a pair of pigeons.

One particular plane the boys learned about had recently been forced to land on a small, remote wilderness lake because of a propeller problem. The pilot scrawled two brief notes, attached a note to each pigeon, then released the birds. Both quickly flew back to the outpost with their urgent message. Another floatplane was dispatched with a replacement propeller, and the original plane and pilot were back at the outpost that same day.

The last few hundred miles of Walt Port’s and Eric Sevareid’s historic canoe trip were the most difficult. With the weather rapidly deteriorating and each day growing steadily colder, ice began forming along the edges of streams. They were so far north now that on clear, star-filled nights, the Aurora Borealis shimmered overhead.

Daily travel became so difficult and stressful that the boys began quarreling over minor issues. One day, a heated disagreement even escalated into an all-out fistfight, the pair rolling over and over on the ground, pummeling each other.

“The same thought must have come to each of us at the same moment,” wrote Sevareid. “And we were sane enough to recognize it in our separate minds: separation here in the wilderness would mean but one thing—death to both. We needed each other as much as we needed food to eat and water to drink. Without speaking a word, we released our holds, staring at each other as if we had been living a bad dream.”

The final test of the journey came when they became hopelessly lost amidst a maze of wilderness lakes, islands, portages and rapids-filled rivers. Had they not stumbled across a Cree family that just happened to be traveling by canoe in the same area, they could very easily have perished. As it was, the family pointed them in the right direction, very possibly saving the boys’ lives. So relieved were they that they now knew where they were, the boys paddled the remaining 60 miles to the shore of Hudson Bay in just 11 hours, arriving at the small settlement of York Factory.

They took a train home, arriving back in Minneapolis on October 11. Five years later, in 1935, the same newspaper that had published their installment stories published a book detailing the adventure. Written by Sevareid, Canoeing with the Cree has since become a classic of American outdoor literature. The last sentence of the book describes the boys’ homecoming and the lasting changes the North country made upon their lives: “It was as though we had suddenly become men and were no longer boys.”

Eric Sevareid (1912-1992) would go on to become a CBS news journalist from 1939 to 1977, and a television commentator on the CBS Evening News for 13 of those years.