The history of firearms is every bit as convoluted, unexpected and occasionally surprising as the history of just about any human endeavor. This #ThrowbackThursday, we're delving into the secret history of firearms for some facts they probably didn't teach you in high school.

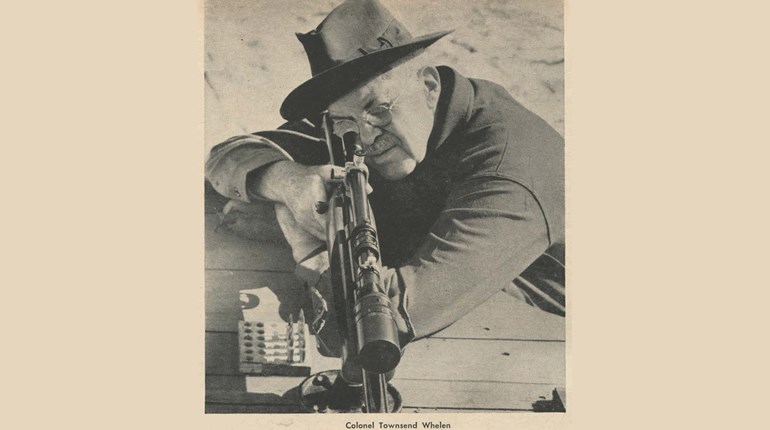

1. Arachnophilic Optics

The famous "crosshairs" you see every time you squint through a riflescope are, these days, usually painstakingly painted on by hand. However, it wasn't always that way. Historically, the material used to make precision optics user-friendly was spider silk—specifically, the silk from female black widow spiders. Why the black widow? Its silk is actually many times stronger than the silk produced by other, less venomous spiders. In fact, the black widow spider produces a thread that is pound-for-pound as strong as Kevlar. That made it perfect for withstanding the force produced by even the most high-powered of firearms. Many optics manufacturers employed one or more people whose sole job was the care and feeding of their captive widows (the going rate was two flies a week). This was actually much tougher on the spiders than it was on the people who handled them: Like most venomous spiders, black widows are fairly mellow critters who only bite humans under provocation...but the burden of constantly producing silk reduced their natural life span by two-thirds.

2. Don Quixote Would Have Approved

The company that almost certainly supplied your childhood BB gun, Daisy Outdoor Products, began life as...a windmill company? It's true: Back in the late nineteenth century, a man named Clarence Hamilton owned the Plymouth Iron Windmill Company. He also operated the Plymouth Air Rifle Company, which was located just around the corner. The windmill company wasn't doing well; transportation costs were eating into profits. The windmill company's board had almost dissolved it when someone got the idea of giving the little air guns away as a premium with each windmill purchase. Plymouth Iron Windmill Company's General Manager L.C. Hough test-fired the gun and exclaimed, "Boy, that's a Daisy." The air rifles were hugely popular...the windmills, not so much. Eventually the windmill company rebranded itself as Daisy Manufacturing Company and, 121 years later, their imprint is on most of our childhood memories.

3. Nothing New Under the Sun

If you spend a lot of time listening to the media these days, you'll get the distinct feeling that firearms capable of firing multiple shots are relatively new. After all, single-shot muskets were good enough for our Revolutionary War forebears, right? Well, no, not exactly. Ever since the first guy touched off a hand cannon (probably in the late thirteenth century, in China), his next thought was no doubt Wouldn't it be great if I could do that again without having to reload? So it really shouldn't be surprised earliest designs for multiple-shot firearms are attributable to the fifteenth-century genius Leonardo da Vinci. As far as actual working models, if you visit the NRA National Firearms Museum, you'll get to observe multiple examples of very early multi-shot long guns and handguns. Above on the right is a French-Persian flintlock gun dating back to the American Revolutionary War, which features multiple rotating chambers that could be pre-loaded with powder and shot. On the left, you'll see an early pistol capable of firing an incredible 18 shots. (Many modern semi-automatic handguns top out at 17.) They were bulky, clunky and people back then simply didn't have the technology to mass-produce them, but multi-shot firearms have been with us for a very long time.

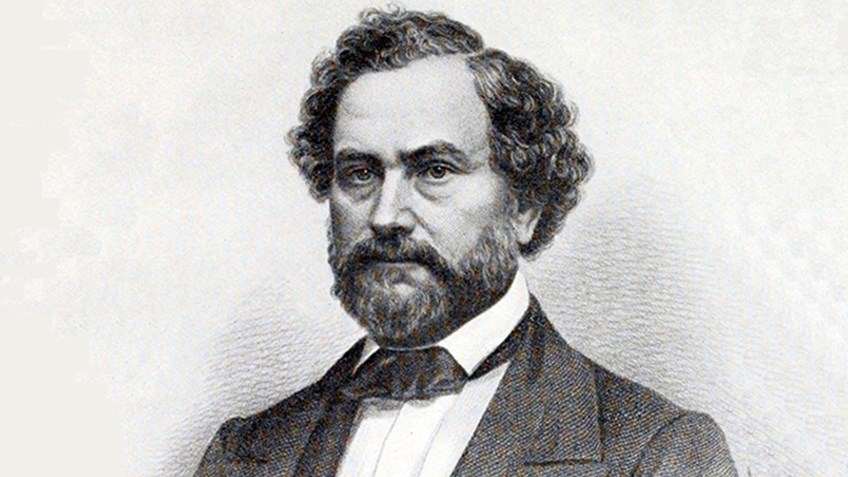

4. And a Child Shall Lead Them

That distinguished-looking gentleman in the above image is Samuel Colt, the man responsible for designing a mass-producible multi-shot gun—the revolver. However, at the time he actually designed it, he probably didn't look quite so distinguished. Then again, who among us does at 16 years old? That's right; Samuel Colt first whittled a wooden model of his idea for a multi-shot handgun, which was based on a ship's wheel, at the age when most of us were primarily worrying about how to cover up our latest crop of pimples. However, even the best ideas don't take off right away, and young Samuel had to wait another five years before he was granted his first patent. In the meantime, he made his living living doing demonstrations...of laughing gas. (What can we say? The year 1832 was a different time.)