Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) was not only America’s 26th president, he was also our most natural-resources-minded chief executive to date—and an avid big-game hunter. But there was one particular bear that Roosevelt refused to shoot. The incident happened in November of 1902, early in his first term as president, when “Teddy,” as he was sometimes called, was on a bear hunting trip to Mississippi.

Guiding the president for several days was none other than Holt Collier, the most famous bear hunter in the state. Born a slave, Collier was now a freed man who made much of his living by bear hunting. During his lifetime, he and his pack of top-notch hounds were said to have taken more than 3,000 black bears.

Yet even as talented a hunter as Collier was, he was having trouble finding a bear for the president, and no doubt feeling the pressure to do so. After several days, Collier’s hounds finally cornered a large male bear and the guide blew his hunting horn, an audible signal for Roosevelt to hurry to Collier’s location.

But before Roosevelt could arrive, the bear killed one of Collier’s hounds. Collier normally would have shot and killed the bear at that point during a hunt, but because he wanted to keep it alive for the president, he lassoed the bear and secured the rope to a tree. However, when Roosevelt arrived and discovered that the bear was tied, he wouldn’t shoot it, stating that it would be unsportsman-like to do so. He also added that such an act would violate his belief in an evolving hunting ethic at the time, known as Fair Chase.

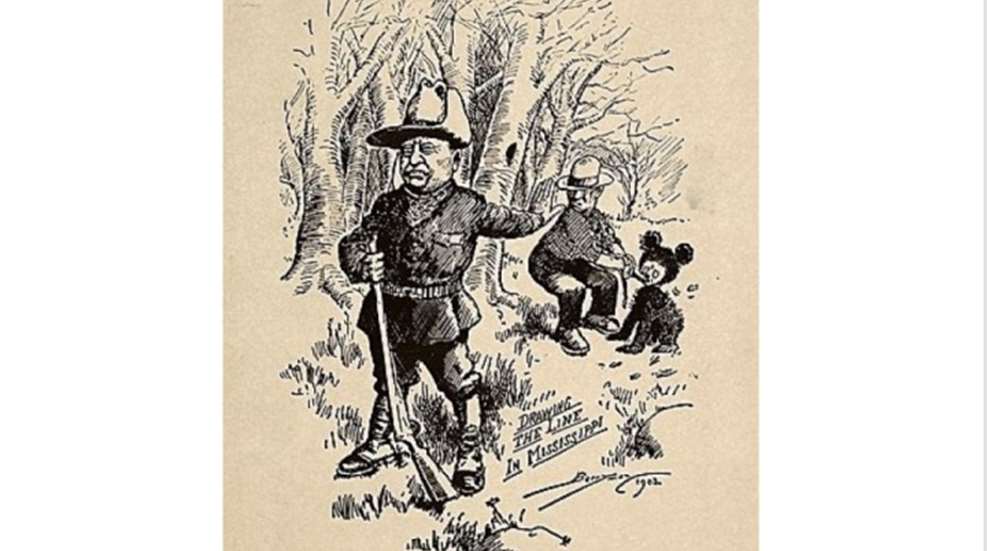

The press quickly picked up the story, running it in the Washington Post and other large eastern newspapers. Accompanying the story was a black and white cartoon sketch titled “Drawing the Line in Mississippi,” picturing Roosevelt refusing to shoot a cub bear being restrained by a man with a rope around its neck.

The account was read by tens of thousands of Americans, likely helping them form a positive opinion of their new president. The story also gave one man, Morris Michtom, a candymaker from Brooklyn, New York, an idea. Michtom asked his wife, a seamstress, to fashion a stuffed toy bear that children might like. His idea was to name the bear in honor of the president—Teddy’s Bear—and sell replicas of the bear in his candy shop. But first, he wanted to get permission from Roosevelt to use his name, so wrote him a letter.

The president responded that he was flattered and had no objections to the proposal. He also added that he didn’t think associating his name with the bear would make much difference. Roosevelt couldn’t have been more wrong. Sales quickly took off, with Michtom eventually founding the Ideal Toy Company as a result. Demand has remained strong ever since—so much so, that in 2002, exactly a century after the bear’s creation, Mississippi named the Teddy bear its official state toy.

Roosevelt’s refusal to shoot the restrained black bear was a public demonstration of his belief in Fair Chase, a set of hunting ethics that he and other visionary sportsmen of the era had been espousing for years. For instance, in 1887, Roosevelt founded the Boone and Crockett Club, named for the legendary hunters and frontiersmen Daniel Boone and David Crockett. A basic tenet of the club was Fair Chase, listing in its constitution the following prohibitions:

- Killing bear, wolf or cougar in traps

- Killing game from a boat while such game is swimming in the water

- Fire-hunting at night (also called jacking or jacklighting)

- Crusting (killing animals immobilized in deep snow)

Today, the prestigious Boone and Crockett Club is North America’s oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization. Through the years, it has refined its definition of Fair Chase, boiling it down to the following one-sentence statement:

“The ethical, sportsmanlike, and lawful pursuit and taking of any free-ranging wild game animal in a manner that does not give the hunter an improper or unfair advantage over the game animals.”

An interesting sidenote to this story is that President Roosevelt was so impressed with Holt Collier’s abilities as a bear hunting guide and outdoorsman that he employed him on a second hunt in 1907, even presenting Collier a Winchester rifle to show his appreciation and gratitude. Collier passed away in 1936 at nearly 90 years of age, and was interred at Greenville, Mississippi. In 2004, a 2,200-acre National Wildlife Refuge located in Mississippi was named in his honor: Holt Collier NWR.