** When you buy products through the links on our site, we may earn a commission that supports NRA's mission to protect, preserve and defend the Second Amendment. **

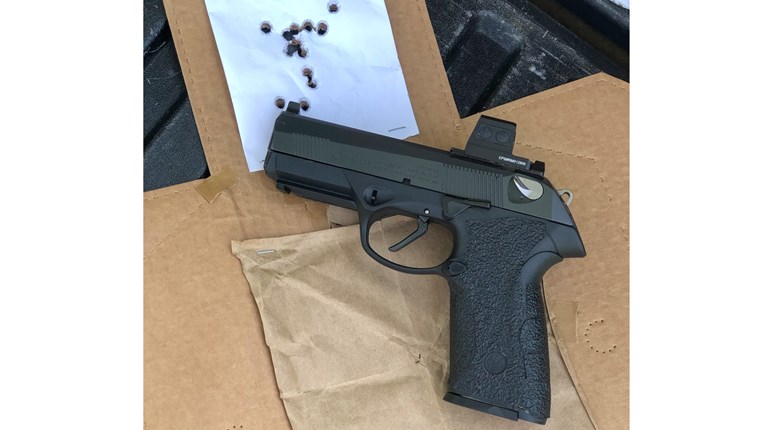

It's easy to understand the reasoning behind most of the rules of gun safety. When you tell a beginner that they must keep their finger off the trigger until they're on target and ready to fire, chances are they won't wonder why. What's more, it's not always important to understand why a rule is a rule, as long as the beginner follows it faithfully. That said, you may have noticed one of the rules of gun safety that we repeat every so often: That you must only use the correct ammunition for your gun. This one might seem a little strange to some people. On the one hand, they might think that using the wrong ammunition would be a difficult mistake to make. On the other hand, they might wonder if it's the same thing as using regular unleaded in a car marked for use with premium...you won't get the best performance, but your car isn't going to explode. Unfortunately, that's not the way it works with firearms, especially with older firearms or ones with iffy maintenance records. Here's why this safety rule is so important.

For the most part, the dimensions of a given cartridge are unique, which in theory ensures that a firearm chamber will accept only one cartridge. In practice, however, dimensional similarities among cartridges as well as the manufacturing tolerances for both guns and ammunition can sometimes permit the wrong cartridge to enter a chamber. When that incorrect cartridge is fired in that chamber, excessive pressures capable of damaging the firearm or injuring the shooter can result.

Generally, there are two types of situations in which this can occur. Most commonly, when there are a number of cartridges based on a single parent case (such as the .25-'06, .280 Rem., .30-'06 and .35 Whelen, all of which are based on the .30-'06 case), it is occasionally possible to chamber a cartridge with a too-large bullet in a chamber of a gun with chamber or throat wear. Should the cartridge be fired in that chamber, excessive pressures would likely result from the attempt to jam an oversized bullet through an undersized bore. In most instances, the differences in neck size will preclude the larger round from entering the smaller chamber, but this may not always be the case with a chamber that has been cut grossly oversize, or when the neck of the cartridge brass has been thinned by turning.

Another dangerous combination may result when a short cartridge is inserted into the chamber of a much larger cartridge of the same head diameter. When this situation is compounded by the shorter cartridge carrying a larger bullet than the bore is designed for, excessive pressures may result. This can be a particular problem with belted magnum cartridges, in which the belt can prevent a shorter cartridge from going deep enough into the chamber to avoid the impact of the firing pin. For example, according to the published data on cartridge and chamber dimensions, a .350 Rem. Mag. cartridge could easily be chambered in an average-dimension chamber for the .300 Wby. Mag. Both are belted magnum cartridges; thus, the .350 Rem. Mag. would be held in proper firing position in the longer .300 Wby. Mag. chamber. If the firing pin were dropped on that cartridge, excessive pressures would be produced when the .358" bullet tried to enter a .308" bore, almost certainly damaging or destroying the rifle. Case splitting and/or an imperfectly sealed chamber might also result, potentially releasing gas into the shooter's face.

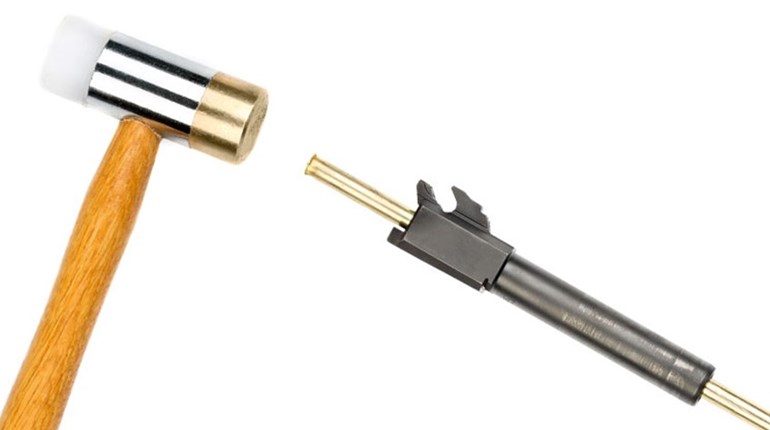

Depending upon the condition of the rifle and the dimensions of the bore and chamber, a shooter may have the potential for such dangerous cartridge/chamber combinations lurking among the firearms he or she owns. A competent gunsmith can diagnose these conditions.

For the most part, the dimensions of a given cartridge are unique, which in theory ensures that a firearm chamber will accept only one cartridge. In practice, however, dimensional similarities among cartridges as well as the manufacturing tolerances for both guns and ammunition can sometimes permit the wrong cartridge to enter a chamber. When that incorrect cartridge is fired in that chamber, excessive pressures capable of damaging the firearm or injuring the shooter can result.

Generally, there are two types of situations in which this can occur. Most commonly, when there are a number of cartridges based on a single parent case (such as the .25-'06, .280 Rem., .30-'06 and .35 Whelen, all of which are based on the .30-'06 case), it is occasionally possible to chamber a cartridge with a too-large bullet in a chamber of a gun with chamber or throat wear. Should the cartridge be fired in that chamber, excessive pressures would likely result from the attempt to jam an oversized bullet through an undersized bore. In most instances, the differences in neck size will preclude the larger round from entering the smaller chamber, but this may not always be the case with a chamber that has been cut grossly oversize, or when the neck of the cartridge brass has been thinned by turning.

Another dangerous combination may result when a short cartridge is inserted into the chamber of a much larger cartridge of the same head diameter. When this situation is compounded by the shorter cartridge carrying a larger bullet than the bore is designed for, excessive pressures may result. This can be a particular problem with belted magnum cartridges, in which the belt can prevent a shorter cartridge from going deep enough into the chamber to avoid the impact of the firing pin. For example, according to the published data on cartridge and chamber dimensions, a .350 Rem. Mag. cartridge could easily be chambered in an average-dimension chamber for the .300 Wby. Mag. Both are belted magnum cartridges; thus, the .350 Rem. Mag. would be held in proper firing position in the longer .300 Wby. Mag. chamber. If the firing pin were dropped on that cartridge, excessive pressures would be produced when the .358" bullet tried to enter a .308" bore, almost certainly damaging or destroying the rifle. Case splitting and/or an imperfectly sealed chamber might also result, potentially releasing gas into the shooter's face.

Depending upon the condition of the rifle and the dimensions of the bore and chamber, a shooter may have the potential for such dangerous cartridge/chamber combinations lurking among the firearms he or she owns. A competent gunsmith can diagnose these conditions.