An icon of America, the Mount Rushmore National Memorial in the Black Hills of South Dakota attracts more than two million visitors annually. Carved on the side of the mountain are the images of four U.S. presidents: Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Lincoln. The monument was sculpted by Gutzon Borglum with help from his son Lincoln, taking them and hundreds of workers 14 years to complete (1927 to 1941).

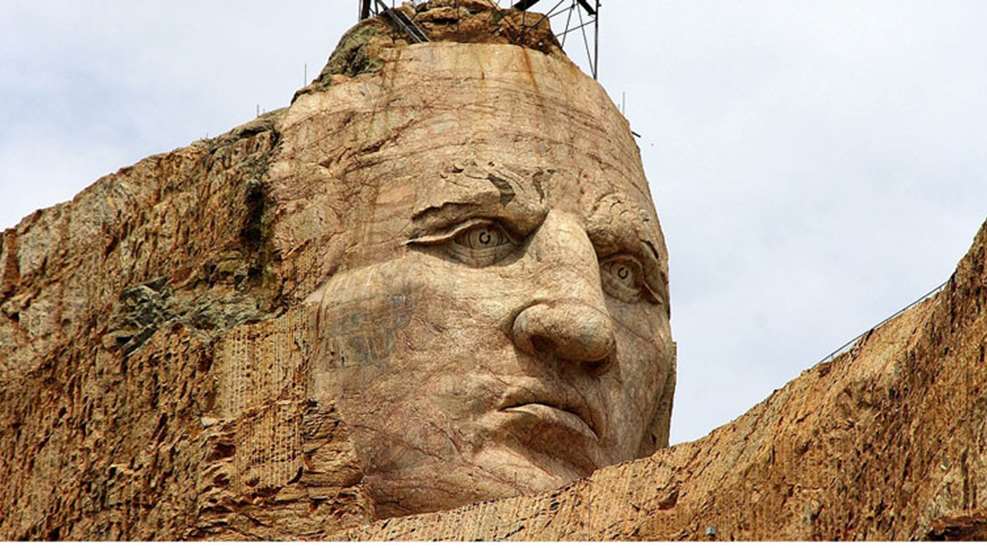

But just 17 miles away stands another, lesser-known memorial, one that honors a Native American icon. Begun in 1948, the monument is still being sculpted into Thunderhead Mountain, but when completed will rival Mount Rushmore in sheer size. It’s known as the Crazy Horse Memorial.

Born circa 1840-1845 on the Northern Plains of North America, Crazy Horse was different from other Indians even from birth. Most Lakota have straight, jet-black hair, but his was dark-brown and wavy, earning him the name Jiji or Light Hair. Such a genetic aberration sometimes occurred in Lakota girls, but seldom in boys. As a result, other Lakota boys teased him mercilessly, a childhood memory they would grow to regret later in life.

Like all Lakota males, Light Hair was raised to be a hunter (provider) and warrior (protector). Boys were given a bow and arrows appropriate for their size at a young age and taught how to use them. After becoming proficient hitting stationary targets, young Lakota boys spent hours playing the Arrows-in-the-Hoop game, shooting arrows through a willow hoop as it rolled along the ground or down a hill. The game taught them how to lead a moving target, a skill they would need as hunters and warriors. When the hoop game became too easy, mentors encouraged the boys to learn to hit flying grasshoppers with their arrows.

Young Lakota males were also expected to become expert horsemen. While riding a pony bareback, most boys in their teens could hit a target with bow and arrow while the horse was running full speed. And once completely trained, a warrior could not only hit a target from a running horse, but could also shoot accurately from beneath the horse’s neck, the technique protecting most of the warrior’s body from enemy fire.

Light Hair excelled at all his lessons, and the tribal elders could tell he would be someone special one day—if he survived. Many young men before him had done well, too, only to be killed early in life because of foolishness in battle. It was a wise warrior who knew how to balance both bravery and boldness. Only time would tell…

Light Hair’s first taste of combat came when he was in his mid-teens. It was to be a horse-stealing raid led by his uncle Spotted Tail against the Pawnee and Omaha tribes, sworn enemies of the Lakota. He stayed close to Spotted Tail as the pair slipped into the enemy’s horse herd undetected and spooked it out of the camp.

As expected, enemy warriors soon swarmed from their tepees to retrieve the horses, and during the ensuing fight an enemy ran toward Light Hair through tall grass. Firing his bow instinctively, Light Hair killed the warrior with a well-placed arrow to the chest. It was only when he approached the dead man to take his scalp that he discovered he had mistakenly killed a young Omaha woman. Shocked and sickened, he said nothing to his fellow warriors about the incident, but was beginning to learn that war did not hold the glory he had expected.

During Light Hair’s second battle against enemy tribes he had his horse shot out from under him, yet managed to kill two enemy warriors, one with his bow and another with a handgun. But that night around the campfire the full impact of the realities of war settled on his shoulders. Light Hair now knew what other warriors knew. A modern-day Lakota, Joseph M. Marshall III, in his 2004 book The Journey of Crazy Horse, explains:

“Ghosts, the old warriors said, were the price a fighting man paid to follow the path of the warrior; somewhere behind the noble and espoused traditions, somewhere behind the achievements and the glory, the ghosts waited. And they would always be there. Their dying would forever be part of the path of the man who took their lives, whether the act was honorable or justified or not. Their faces, and often their dying moments, could not be forgotten, unless the heart of the warrior was made of stone. And few could boast of that, though many might have secretly wished it to be so. Somewhere people they didn’t know—wives and daughters, mothers and grandmothers—would mourn. They would wail and gash themselves, their hearts torn in anguish. The path of the warrior was indeed strewn with broken hearts, like so many stones on a long and winding trail.”

Light Hair pushed those thoughts from his mind as he grew older, gradually becoming more and more the seasoned warrior. After all, had he not done what had been expected of him? Had he not fought to protect his people, the Lakota? And something else happened that made it all easier to accept. His father was now very proud of him—he had a son who had become a mighty warrior. To mark the occasion his father conducted a formal ceremony, changing Light Hair’s name to Crazy Horse.

Embracing the warrior way of life from that time forward, Crazy Horse would go on to become one of the Lakota’s greatest war leaders. He participated in many battles during the years to come, but the three for which he’s most remembered were those fought against soldiers of the United States Army. During the Battle of the Rosebud (1876), casualties on both sides were about equal, but during the Fetterman Fight (1866) and Battle of the Little Big Horn (1876), the Army detachments were completely wiped out.

Euro-Americans had been encroaching on Lakota lands for years, and the U.S. government continued to send troops west to protect the ever-increasing number of wagon trains from hostile tribes. As a result, Crazy Horse eventually realized he was fighting a battle of attrition, and that white soldiers were like leaves on the trees. No matter how many fell one year, more would come the following year to replace them.

Crazy Horse and his nearly 1,000 followers finally ceased hostilities and turned themselves in to government authorities at the Red Cloud Agency near Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in May of 1877, becoming reservation Indians. Only Sitting Bull and his Hunkpapa band remained “wild” Lakota, and they had fled to Canada.

Four months later, Crazy Horse was arrested under the pretense of stirring trouble and escorted to the guard house at Fort Robinson. But when Crazy Horse realized he was being imprisoned, a scuffle ensued and he was stabbed in the chest by a soldier armed with a rifle equipped with a bayonet. Crazy Horse lingered a few hours but died later that night, not yet 40 years old.

Ironically, 105 years later (1982), Crazy Horse was honored by the U.S. Postal Service, his image printed on a 13-cent Great Americans series postage stamp.