Standing 5 feet, 10 inches tall and soft-spoken, he was a member of the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806). And you would think that after those years of severe deprivation, tremendous hardship, and extreme danger anyone would be ready for a well-deserved rest. Not John Colter.

As the expedition was making its way back down the Missouri River, and just six weeks from St. Louis, it was met by two men headed upstream: Forest Hancock and Joseph Dickson. The pair said they planned to trap beaver in the upper Missouri River country and needed a guide. John Colter stepped forward.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark agreed to release Colter from the expedition nearly two months early, as long as none of the other crew members wanted to do the same. All was agreed to, Colter was honorably discharged, and he, Hancock and Dickson headed west, back toward the “Shining Mountains.”

But their partnership was short-lived, possibly only a few months. Dissatisfied, Colter left the other two men and was headed east when he encountered another group of trappers led by trader and businessman Manual Lisa. The group included several members of the original Lewis and Clark party, and they convinced Colter to join them. So this time, when he was just a week away from St. Louis, Colter once again headed west.

At the confluence of the Yellowstone and Bighorn Rivers the men built Fort Raymond. Lisa then sent Colter in search of members of the Crow Indian tribe living in the area, to let them know the fort was open for trade in beaver pelts or “plews” as the trappers called the furs. It was during his wilderness search for Indians that Colter wandered into what one day would become Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. And what is amazing about his journey is that he made it alone, during the dead of winter, in an area known for its deep snows and temperatures of 30 degrees below zero, not including wind-chill.

Upon returning to Fort Raymond the next spring (1808), Colter’s reports of geysers spewing high into the air, bubbling mudpots, and steaming pools of water were just too much for most of the other trappers to believe. They jokingly referred to the area as “Colter’s Hell,” and it wasn’t until years later that Colter was proven right. Of course, Native Americans living in the region had known Colter was telling the truth all along, but no one had bothered to ask them.

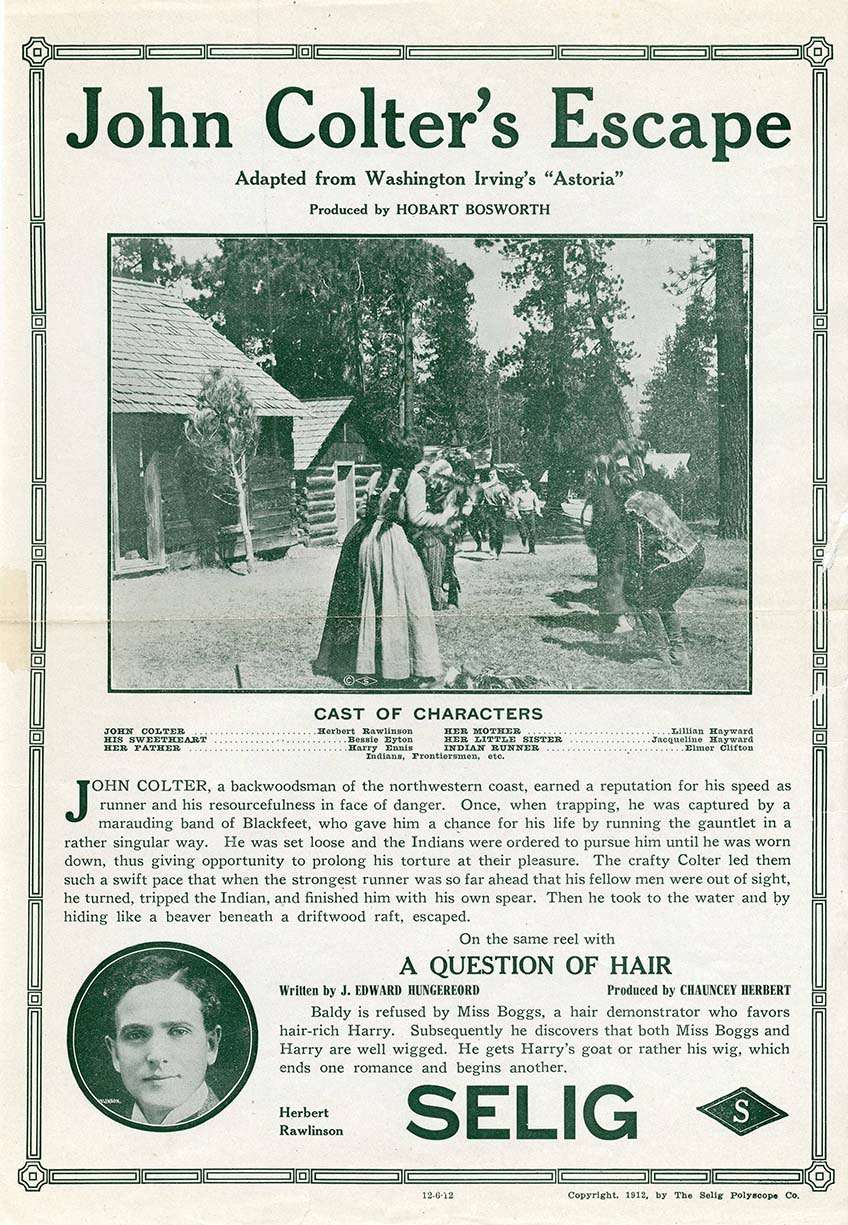

The greatest adventure of John Colter’s life came a year later when he teamed up with John Potts, yet another former member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The pair was paddling a canoe up the Jefferson River, beaver trapping, when they were surprised by a large group of hostile Blackfoot Indians along the bank.

The Indians ordered the two trappers ashore and Colter complied, but Potts did not, remaining in the canoe. Angered, an Indian fired his rifle at Potts, wounding him in the shoulder. Potts returned fire, killing the Indian. Now enraged, the other Indians immediately riddled Potts with bullets, dragged his dead body ashore and hacked it to pieces, throwing the bloody pieces in Colter’s face.

No doubt, Colter thought he, too, would soon be killed, but after a quick council held by the Indian leaders, one of the chiefs approached Colter and asked him if he was a good runner. “Not very…” Colter lied. In short order, he was stripped naked and told to run.

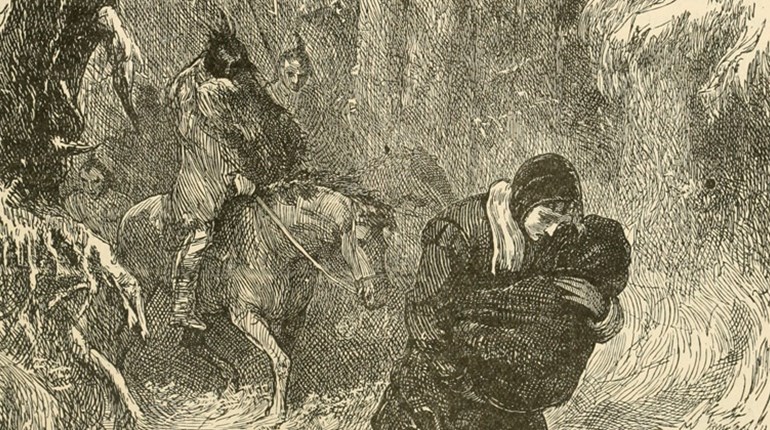

Colter may have briefly thought he was being given a reprieve, but when he saw the young warriors of the tribe unburdening themselves of all but their weapons, he knew he was in a race for his life. Colter was given only a short head start before dozens of howling braves charged after him in pursuit.

Colter’s famous run took place on a flat plain covered with prickly pear cactus. He ignored the pain in his bare feet as he kept running. After several miles, a blood vessel burst in his nose, and blood began dripping down across his lips, onto his chin, and splattering onto his chest and legs. Even then he kept running, his legs pumping, his chest heaving, knowing that to stop meant certain death.

But eventually Colter began to falter, and glancing over his shoulder saw only one Indian close by, the rest far behind. Finally, Colter made the decision to turn, face his attacker, and fight it out.

With blood pouring from his nose and covering the front of his naked body, Colter must have been a ghastly sight. Whatever the reason, the warrior stumbled when he attempted to throw the spear he was carrying, which stuck in the ground near Colter’s feet. Quickly snatching up the weapon, Colter ran his attacker through, pinning him to the ground, and resumed the race.

Eventually arriving at the Madison River five miles from where he had started, Colter swam to an island and ducked under a large pile of driftwood. There he hid the remainder of the day with just his head above water, the Indians searching the banks of the river and the island, even climbing atop the pile of driftwood at one point. Hours after dark, Colter swam out from his hiding place and escaped.

But even though the Indians were no longer a threat, his ordeal was not yet over. It took Colter the next eleven days to walk to a trading post on the Little Big Horn River, eating plants and roots he found along the way to survive. When he finally arrived back at Manual Lisa’s trading post, the other trappers hardly recognized him.

Believing his luck may finally be running out, Colter left the western wilderness and returned to St. Louis in 1810, having been away from civilization for six years. He subsequently bought a farm near New Haven, Missouri, and eventually married. All we know of his wife was that she was named either Sally or Sallie.

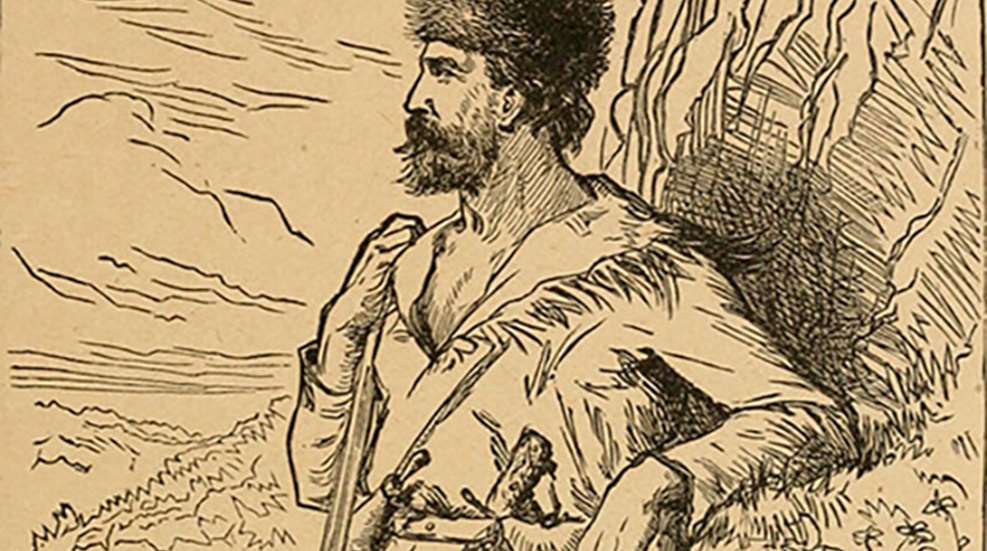

It is also not known for sure when John Colter died or from what cause. One source says he was suddenly taken ill and died in bed of jaundice on May 7, 1812. Another source cites November 22, 1813. Either way, John Colter—trapper, explorer, frontiersman—has long been considered the American West’s first mountain man.