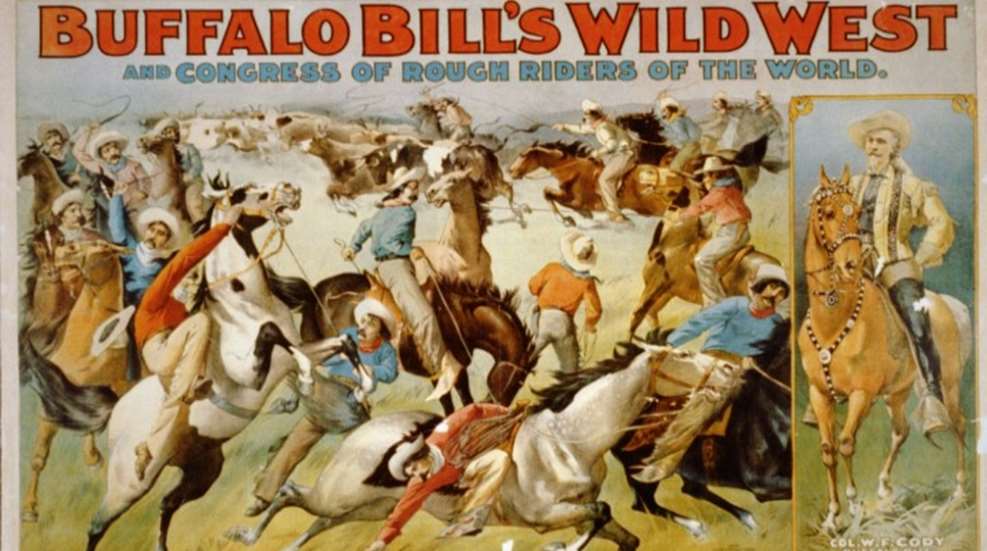

Some historians contend that at the turn of the 20th Century, William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody (1846–1917) was the most recognizable celebrity on earth. True or not, much of that worldwide fame resulted from the 30 years his annual traveling extravaganza—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West—toured North America, England and Europe, performing some 300 shows per year. A circus-like troupe employing hundreds of people, Cody’s Wild West featured real cowboys, authentic Indians, stampeding bison, bucking broncos, runaway stagecoaches and even sharpshooters such as the legendary Calamity Jane and Annie Oakley.

Born in Le Clair, Iowa, Cody worked at many jobs during his younger years: Pony Express rider, Civil War soldier, and civilian scout for the U. S. Army, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1872.

He earned his nickname, Buffalo Bill, shortly after the Civil War when he signed a contract to supply Kansas Pacific Railroad workers with buffalo meat from the massive herds of bison grazing the Great Plains during the 1800s. Cody was so adept as a hunter that during one 18-month period in 1867 and 1868, he is purported to have killed 4,282 of the large, wooly animals.

But another hunter, Bill Comstock, challenged Cody’s right to exclusive use of the nickname "Buffalo Bill." The pair agreed to an eight-hour bison hunt to settle the matter. Cody won by shooting 68 buffalo compared to Comstock’s 48. (As a sidenote, it is believed Comstock used a .44-caliber Henry lever-action rifle, while Cody used a .50-caliber Springfield Model 1866.)

With the eventual demise of the bison herds, Cody watched firsthand as other changes quickly began taking place in the American West. The once free-roaming Native American Indian tribes were confined to reservations. Barbed wire was stretched mile after mile across the plains, dividing the land into farms and ranches. And railroad tracks now crisscrossed the prairies, the “iron horse” bringing more and more settlers and tourists west with it each year.

As a frontiersman Cody regretted the changes, but as a natural-born showman and entrepreneur he could also see that the American public back East was fascinated and intrigued by the rapidly vanishing American West. He sensed there was money to be made on that theme, and as a result put together the initial version of his Wild West in 1883.

Opening May 17 in Omaha, Nebraska, to positive reviews, the show next moved on to Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Indiana, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts. By July, the troupe was at the Prospect Fairgrounds in Brooklyn. When it reached Coney Island in August, Cody decided to erect bleachers for the audience and perform there for five weeks. In a letter to his relatives back in Iowa, he wrote:

“Have went to a big expense fitting up a place here…it won’t be much this year, but will be good for next. I am not much ahead on the summer in cash, but I have my show all clear and a fine place built here. I have over a hundred head of stock—ten head of fine race horses, the finest six-mule coach train in the world, and seventy head of good saddle horses—and the foundation laid for a fortune before long. The papers say I am the coming Barnum.”

The Wild West’s first really successful season was 1885, when it was viewed by more than one million people and cleared a profit of $100,000, equivalent to millions in today’s dollars. In 1886, Cody decided that instead of the show constantly moving from one location to another, he would book into the Erastina resort on Staten Island, New York, where 20,000 people could watch two daily three-hour performances scheduled for 12:30 and 7:00 p.m., the later show taking place under the lights.

Cody was constantly adding new attractions to the Wild West, one of which was the Lakota Indian chief Sitting Bull, who toured four months during the summer of 1885. Keep in mind that it was Sitting Bull and his warriors who had wiped out General Custer and his soldiers at the Little Big Horn in 1876, just nine years prior. As a result, Sitting Bull was often hissed at and booed by audiences when he was introduced. Of Sitting Bull, Cody remembered:

“He never did more than appear on horseback at any performance and always refused to talk English, even if he could. At Philadelphia, a man asked him if he had no regret at killing Custer and so many whites. He replied, ‘I have answered to my people for the Indians slain in the fight. The chief that sent Custer must answer to his people.’ That is the only smart thing I ever heard him say. He was a peevish Indian…”

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West jumped the pond for the first time in 1887, touring Europe until 1892, then again from 1902 to 1906. The troupe performed before various kings, queens and other royalty, with Cody even meeting Pope Leo XIII in 1890. In May of 1892, a command performance was held before Queen Victoria at an improvised arena at Windsor Castle.

An insightful anecdote of the European tour occurred in Barcelona, Spain. Upon seeing the large statue erected there of Christopher Columbus, one Indian made the terse comment, “It was a d_____ bad day for us when he discovered America.”

As might be imagined, life on the road was often not easy for Cody and his entourage. At the peak of the show’s popularity, it took some 700 people to make it all happen: performers, blacksmiths, canvasmen, electricians, musicians, cooks, watchmen, porters and many others. It also required 52 railroad cars to transport all those people, gear and livestock thousands of miles annually.

Traveling so many miles each year, train accidents were inevitable. The worst occurred on the night of October 28, 1901, while en route to Danville, Virginia, the last show of the season. A train engineer had pulled his freight onto a siding to allow the Wild West train to pass, then pulled back onto the main track. However, what he did not realize was that the show train consisted of three sections. At 3:20 a.m., the engineer saw the headlight of the engine pulling the second section of the show train rapidly approaching. The crews of both trains were able to jump to safety just before the two locomotives collided in a spectacular crash.

Thankfully, no humans were killed, but 110 horses either died outright or had to be put down. Two of Cody’s favorite mounts were shot, Old Pap and Old Eagle. One investigator sent by the Southern Railroad to help clear the train wreckage stated, “The two engines seemed to have tried to devour each other.”

Unfortunately, Annie Oakley was severely injured in the accident, her injuries requiring surgery and hospitalization for months. She eventually recovered, but not fully. Essentially her involvement with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West ended that dark autumn night.

The show would continue on for 12 more years, before finally closing in 1913 due to bankruptcy. Buffalo Bill Cody passed away four years later, January 10, 1917, of uremic poisoning, kidney failure. Annie Oakley said of him in a tribute to his Wild West:

“I traveled with him for 17 years—there were thousands of men in the outfit during that time. Comanches, cowboys…every kind of person. And the whole time we were one great family, loyal to him.

“He called me ‘Missie’ almost from the first, a name I have been known by to my intimate friends ever since. In those days, we had no train of our own. No elaborate outfit, not even any shelters, except a few army tents to dress in. Among ourselves it was more like a clan than a show. Buffalo Bill, his two hundred friends and companions, a bunch of longhorns and buffalo, would come to town and show what life was like where they came from. That was all it was. That is what took—the essential truth and good spirit of the game made it the foremost educational performance ever given in the world.”